Conjure Oxide

Welcome to the documentation of Conjure Oxide, a next generation constraints modelling tool written in Rust. It supports models written in the Essence and Essence Prime constraints modelling languages.

Conjure Oxide is in the early stages of development, so most Essence language features are not supported yet. However, it does currently support most of Essence Prime.

This site contains the user documentation for Conjure Oxide; other useful links can be found on the useful links page.

Contributing

The project is primarily developed by students and staff at the University of St Andrews, but we also welcome outside contributors; for more information see the contributor's guide.

Licence

The Conjure Oxide source and documentation are released under the Mozilla Public Licence v2.0.

Installation

To install Conjure Oxide, either build it from source, or use a nightly release.

Logging

This document is a work in progress - for a full list of logging options,

see Conjure Oxide's --help output.

To stderr

Using --verbose, and the RUST_LOG environment variable, you can control the

contents, and formatting of, Conjure Oxide's stderr output:

-

--verbosechanges the formatting of the logs for improved readability, including printing source locations and line numbers for log events. It also enables the printing of the log levelsINFOand above. -

The

RUST_LOGenvironment variable can be used to customise the log levels that are printed depending on the module . For more information, see: https://docs.rs/env_logger/latest/env_logger/#enabling-logging.

Example: Logging Rule Applications

Different log levels provide different information about the rules applied to the model:

-

INFOprovides information on the rules that were applied to the model. -

TRACEadditionally prints the rules that were attempted and why they were not applicable.

To see TRACE logs in a pretty format (mainly useful for debugging):

$ RUST_LOG=trace conjure-oxide solve --verbose <model>

Or, using cargo:

$ RUST_LOG=trace cargo run -- solve --verbose <model>

Contributors Guide

We love your input! We want to make contributing to this project as easy and transparent as possible, whether it's:

- Reporting a bug

- Discussing the current state of the code

- Submitting a fix

- Proposing new features

- Becoming a maintainer

Contributing

This project is open-source: you can find the source code on Github, and issues, questions, or feature requests can be posted on the Github issue tracker.

Currently, Conjure Oxide has been primarily developed by students and staff at the University of St Andrews. That being said, we welcome and encourage contributions from individuals outside the University. Over the course of this section, we will expand further into how you can contribute.

For more detailed information reguarding our contributing process, please refer to CONTRIBUTING.md

Licence

This project is entirely open-source, with all code released under the MPL 2.0 license, unless stated otherwise.

This section had been adapted from the 'home' page of the conjure-oxide wiki, and CONTRIBUTING.md

How We Work

This is our Constitution, but in contrast to a real constitution of a company we intend this document to be a living document. Please feel free to suggest edits and improvements.

Principles

- Assume good faith.

- Take responsibility for your work.

- Look for opportunites to help others.

- Make it easy for others to help you.

Social contract

We agree to adhere to the following guidelines when engaging in group work.

- We communicate in English as a common, shared language.

- We include all group members in meetings, group chats, messages, and social events.

- We turn up on time to meetings.

- We pay attention and contribute to group discussions.

- We contribute to the group tasks.

- We listen to each other’s opinions.

- We share ideas and do not disregard other people’s thoughts or feelings.

- We are respectful towards one another and treat each other with care and courtesy.

- We complete tasks on time and to the best of our ability.

- We do not make assumptions about individual abilities.

Logistics

- GitHub: We use GitHub as our main platform for code collaboration and version control.

- Teams: We use Teams for day to day communications.

- Weekly report: We use a web form to provide an update to the supervisors every week. This is not assessed and doesn't strictly follow the reflective writing methods. However, this resource on the Gibbs reflective cycle may still be helpful when approaching the weekly form and how to use the form effectively.

- Weekly meetings: The whole group meets once a week. Before this meeting everyone fills in the weekly report. We take minutes at these meetings.

Best Practices for Collaboration

1. Start with Early Pull Requests (PRs)

- Don’t wait until everything is perfect; submitting early PRs allows the team to provide feedback sooner. This helps catch potential issues early and encourages collaboration.

- Even if your code isn’t complete, opening a draft PR can be a good way to start discussions and ensure alignment.

2. Show, Don’t Tell

- Share your experiences and insights! Use GitHub or Microsoft Teams to share updates, challenges, and breakthroughs with the rest of the team.

- Showing real examples means other can more easily help you, it can help others understand your approach and may inspire new ideas.

- High-level explanations can inadvertantly hide important details. Showing the actual artefact (whether it's code, a design document or something else) together with your high-level commentary eliminates this risk.

3. Begin with Specifications

- Before you start coding, document your plan. Write out specifications or create a rough outline of what you're working on, including examples where possible.

- Having a clear plan makes it easier to get feedback and helps others understand the purpose and scope of your work.

4. Share Failures as Much as Successes

- When something doesn’t work, share it! Learning from mistakes and discussing setbacks is invaluable.

- A failed attempt can often be as educational as a successful one, and it may prevent others from encountering the same issue.

5. Ask Good Questions

- Don’t hesitate to reach out when you're stuck, but try to ask thoughtful, specific questions.

- Providing context and sharing what you've tried will help others give more helpful answers.

Final Thoughts

- Collaboration is key to our success, so feel free to communicate openly.

- Continuous improvement is encouraged—keep looking for ways to improve your code, processes, and knowledge.

This section had been taken from the 'How we work' page of the conjure-oxide wiki

Setting up your development environment

Conjure Oxide supports Linux and Mac.

Windows users should install WSL and follow the Linux (Ubuntu) instructions below:

Linux (Debian/Ubuntu)

The following software is required:

- The latest version of stable Rust, installed using Rustup.

- A C/C++ compilation toolchain and libraries:

- Debian, Ubuntu and derivatives:

sudo apt install build-essential libclang-dev - Fedora:

sudo dnf group install c-developmentandsudo dnf install clang-devel

- Debian, Ubuntu and derivatives:

- Conjure.

- Ensure that Conjure is placed early in your PATH to avoid conflicts with ImageMagick's

conjurecommand!

- Ensure that Conjure is placed early in your PATH to avoid conflicts with ImageMagick's

MacOS

The following software is required:

St Andrews CS Linux Systems

-

Download and install the pre-built binaries for Conjure. Place these in

/cs/home/<username>/usr/binor elsewhere in your$PATH. -

Install

rustupand the latest version of Rust throughrustup. The school provided Rust version does not work.- By default,

rustupinstalls to your local home directory; therefore, you may need to re-installrustupand Rust after restarting a machine or when using a new lab PC.

- By default,

Improving Compilation Speed

Installing sccache improves compilation speeds of this project by caching crates and C/C++ dependencies system-wide.

- Install sccache and follow the setup instructions for Rust. Minion detects and uses sccache out of the box, so no C++ specific installation steps are required.

This section had been taken from the 'Setting up your development environment' page of the conjure-oxide wiki

"Omit needless words"

(c) William Strunk

Key Points

Resources

See:

Do's

Our documentation is inline with the code. The reader is likely to skim it while scrolling through the file and trying to understand what it does. So, our doc strings should:

- Be as brief and clear as possible

- Ideally, fit comfortably on a standard monitor without obscuring the code

- Contain key information about the method / structure, such as:

- A single sentence explaining its purpose

- A brief overview of arguments / return types

- Example snippets for non-trivial methods

- Explain any details that are not obvious from the method signature, such as:

- Details of the method's "contract" that can't be easily encoded in the type system

(E.g: "The input must be a sorted slice of positive integers"; "The given expression will be modified in-place")

- Non-trivial situations where the method may

panic!or cause unintended behaviour(E.g: "Panics if the connection terminates while the stream is being read")

- Any

unsafethings a method does(E.g: "We type-cast the given pointer with

mem::transmute. This is safe because...") - Special cases

- Details of the method's "contract" that can't be easily encoded in the type system

Don'ts

Documentation generally should not:

- Repeat itself

- Use long, vague, or overly complex sentences

- Re-state things that are obvious from the types / signature of the method

- Explain implementation details

- Explain high-level architectural decisions (Consider making a wiki page or opening an RFC issue instead!)

And finally... Please, don't ask ChatGPT to document your code for you! I know that writing documentation can be tedious, but you can always:

- Write a one-sentence doc string for now and come back to it later

- Ask others if you don't quite understand what a method does

Types and Tests are Documentation

Documentation is great, but we should also use the type system and other rust features to our advantage!

-

A lot of things (e.g: error conditions, thread safety, state) can be encoded in the types of arguments / return values. This is usually better than just

panic!-ing and adding a doc string to explain why. -

Tests are also a great way to illustrate the behaviour of your code and any special cases - and they also help with catching bugs!

Example Snippets

For non-trivial methods and user-facing API's, it may be useful to include an example. Examples should be minimal but complete snippets of code that illustrate a method's behaviour.

If you wrap your example in a code block:

```rust ... ```

Our CI will even run it and complain if the example does not compile / contains an error!

However, don't feel obliged to include an example for every method! For simple methods they may not be necessary.

Examples

⚠️ Good but a bit wordy:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { /// Checks if the OPTIMIZATIONS environment variable is set to "1". /// /// # Returns /// - true if the environment variable is set to "1". /// - false if the environment variable is not set or set to any other value. fn optimizations_enabled() -> bool { match env::var("OPTIMIZATIONS") { Ok(val) => val == "1", Err(_) => false, // Assume optimizations are disabled if the environment variable is not set } } }

✅ Since everything else is obvious from the signature, we can just say:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { /// Checks if the OPTIMIZATIONS environment variable is set to "1" fn optimizations_enabled() -> bool { ... } }

⚠️ Not bad, but sounds a bit robotic

# Side-Effects

- When the model is rewritten, related data structures such as the symbol table (which tracks variable names and types)

or other top-level constraints may also be updated to reflect these changes. These updates are applied to the returned model,

ensuring that all related components stay consistent and aligned with the changes made during the rewrite.

- The function collects statistics about the rewriting process, including the number of rule applications

and the total runtime of the rewriter. These statistics are then stored in the model's context for

performance monitoring and analysis.

✅ Same idea but shorter

# Side-Effects

- Rules can apply side-effects to the model (e.g. adding new constraints or variables).

The original model is cloned and a modified copy is returned.

- Rule engine statistics (e.g. number of rule applications, run time) are collected and stored in the new model's context.

⚠️ A bit too detailed

# Parameters

- `expression`: A reference to the [`Expression`] that will be evaluated against the given rules. This is the main

target for rule transformations and is expected to remain unchanged during the function execution.

- `model`: A reference to the [`Model`] that provides context for rule evaluation, such as constraints and symbols.

Rules may depend on information in the model to determine if they can be applied.

- `rules`: A vector of references to [`Rule`]s that define the transformations to be applied to the expression.

Each rule is applied independently, and all applicable rules are collected.

- `stats`: A mutable reference to [`RewriterStats`] used to track statistics about rule application, such as

the number of attempts and successful applications.

✅ Just describing the meaning of arguments will do

(Details of the rewriting process belong on the wiki, and details of underlying types such as Model or Expression are already documented next to their implementations)

- `expression`: A reference to the [`Expression`] to evaluate.

- `model`: A reference to the [`Model`] for access to the symbol table and context.

- `rules`: A vector of references to [`Rule`]s to try.

- `stats`: A mutable reference to [`RewriterStats`] used to track the number of rule applications and other statistics.

This section had been taken from the 'Documentation Style' page of the conjure-oxide wiki

"Omit needless words"

(c) William Strunk

Key Points

Resources

See:

Do's

Our documentation is inline with the code. The reader is likely to skim it while scrolling through the file and trying to understand what it does. So, our doc strings should:

- Be as brief and clear as possible

- Ideally, fit comfortably on a standard monitor without obscuring the code

- Contain key information about the method / structure, such as:

- A single sentence explaining its purpose

- A brief overview of arguments / return types

- Example snippets for non-trivial methods

- Explain any details that are not obvious from the method signature, such as:

- Details of the method's "contract" that can't be easily encoded in the type system

(E.g: "The input must be a sorted slice of positive integers"; "The given expression will be modified in-place")

- Non-trivial situations where the method may

panic!or cause unintended behaviour(E.g: "Panics if the connection terminates while the stream is being read")

- Any

unsafethings a method does(E.g: "We type-cast the given pointer with

mem::transmute. This is safe because...") - Special cases

- Details of the method's "contract" that can't be easily encoded in the type system

Don'ts

Documentation generally should not:

- Repeat itself

- Use long, vague, or overly complex sentences

- Re-state things that are obvious from the types / signature of the method

- Explain implementation details

- Explain high-level architectural decisions (Consider making a wiki page or opening an RFC issue instead!)

And finally... Please, don't ask ChatGPT to document your code for you! I know that writing documentation can be tedious, but you can always:

- Write a one-sentence doc string for now and come back to it later

- Ask others if you don't quite understand what a method does

Types and Tests are Documentation

Documentation is great, but we should also use the type system and other rust features to our advantage!

-

A lot of things (e.g: error conditions, thread safety, state) can be encoded in the types of arguments / return values. This is usually better than just

panic!-ing and adding a doc string to explain why. -

Tests are also a great way to illustrate the behaviour of your code and any special cases - and they also help with catching bugs!

Example Snippets

For non-trivial methods and user-facing API's, it may be useful to include an example. Examples should be minimal but complete snippets of code that illustrate a method's behaviour.

If you wrap your example in a code block:

```rust ... ```

Our CI will even run it and complain if the example does not compile / contains an error!

However, don't feel obliged to include an example for every method! For simple methods they may not be necessary.

Examples

⚠️ Good but a bit wordy:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { /// Checks if the OPTIMIZATIONS environment variable is set to "1". /// /// # Returns /// - true if the environment variable is set to "1". /// - false if the environment variable is not set or set to any other value. fn optimizations_enabled() -> bool { match env::var("OPTIMIZATIONS") { Ok(val) => val == "1", Err(_) => false, // Assume optimizations are disabled if the environment variable is not set } } }

✅ Since everything else is obvious from the signature, we can just say:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { /// Checks if the OPTIMIZATIONS environment variable is set to "1" fn optimizations_enabled() -> bool { ... } }

⚠️ Not bad, but sounds a bit robotic

# Side-Effects

- When the model is rewritten, related data structures such as the symbol table (which tracks variable names and types)

or other top-level constraints may also be updated to reflect these changes. These updates are applied to the returned model,

ensuring that all related components stay consistent and aligned with the changes made during the rewrite.

- The function collects statistics about the rewriting process, including the number of rule applications

and the total runtime of the rewriter. These statistics are then stored in the model's context for

performance monitoring and analysis.

✅ Same idea but shorter

# Side-Effects

- Rules can apply side-effects to the model (e.g. adding new constraints or variables).

The original model is cloned and a modified copy is returned.

- Rule engine statistics (e.g. number of rule applications, run time) are collected and stored in the new model's context.

⚠️ A bit too detailed

# Parameters

- `expression`: A reference to the [`Expression`] that will be evaluated against the given rules. This is the main

target for rule transformations and is expected to remain unchanged during the function execution.

- `model`: A reference to the [`Model`] that provides context for rule evaluation, such as constraints and symbols.

Rules may depend on information in the model to determine if they can be applied.

- `rules`: A vector of references to [`Rule`]s that define the transformations to be applied to the expression.

Each rule is applied independently, and all applicable rules are collected.

- `stats`: A mutable reference to [`RewriterStats`] used to track statistics about rule application, such as

the number of attempts and successful applications.

✅ Just describing the meaning of arguments will do

(Details of the rewriting process belong on the wiki, and details of underlying types such as Model or Expression are already documented next to their implementations)

- `expression`: A reference to the [`Expression`] to evaluate.

- `model`: A reference to the [`Model`] for access to the symbol table and context.

- `rules`: A vector of references to [`Rule`]s to try.

- `stats`: A mutable reference to [`RewriterStats`] used to track the number of rule applications and other statistics.

This section had been taken from the 'Crate Structure' page of the conjure-oxide wiki

2023‐11: High Level Plan

This page is a summary of discussions about the architecture of the project circa November 2023.

In brief:

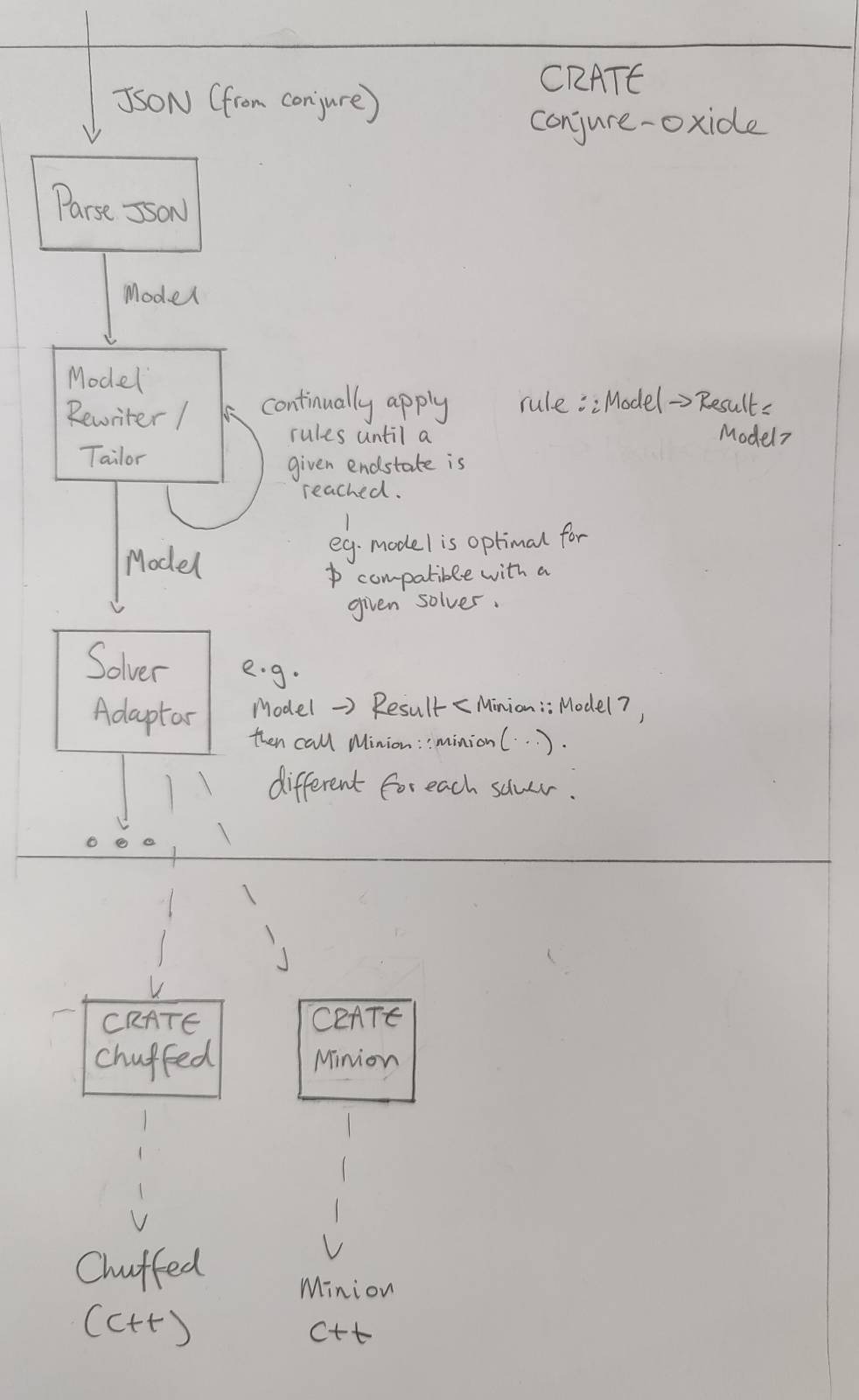

Conjure Oxide

Model Rewriting Engine

The purpose of the model rewriting engine is to turn a high level constraints model into one that can be run by various solvers. It incrementally rewrites a given model by applying a series of rules.

Rules have the type:

rule :: fn(Expr) -> Result<Expr,Error>

The use of Result here allows for the type checking of the Model at each stage (amongst other things).

A sketch of a rewriting algorithm is below. As we are using a Result type, backtracks occur when an Err is returned.

fn apply(rules,x) {

new_rules = getApplicable(rules)

if shouldStop(x) {

return Ok(x)

}

// Recursive case - multiple rules

while len(rules') > 0 {

rule = select(new_rules)

new_rules.remove(rule)

res = apply(rules,rule(x))

if res is Ok, return Ok

}

// No rules - base case

if (compatibleWithSolver(x)) {

return Ok(x)

}

return Err()

}

This is, in effect, a recursive tree search algorithm. The behaviour of the search can be changed by changing the following functions:

- getApplicable:

fn(Vec<Rule>) -> Vec<Rule> - select:

fn(Vec<Rule>) -> Vec<Rule> - shouldStop:

fn(x) -> bool

The following functions are also important to implement the rewriting engine:

domainOf:: Expr -> Domain

typeOf:: Expr -> Type

typeOfDomain:: Domain -> Type

categoryOf:: Expr -> Category

data Category = Decision | Unknown | Quantified

Solver Adaptors

Once we have a Model object that only uses constraints supported by a particular solver, we are able to translate it to a form the solver understands.

The solver adaptor layer translates a Model into solver specific data-structures, and then runs the solvers.

If the given Model isn't compatible with the solver, the use of a Result type here could allow a type error to be thrown.

Other crates inside this repository

This repository contains the code for Conjure Oxide as well as the code for some of its dependencies and related works.

Currently, these are just Rust crates that provide low level bindings to various solvers.

There should be a strict separation of concerns between each crate and Conjure Oxide. In particular, each crate in this project should be considered a separate piece of work that could be independently published and used. Therefore:

- The crate should have its own complete documentation and examples.

- The public API should be safe and make sense outside the context of Conjure Oxide.

Solver Crates

Each solver crate should have a API that matches the data structures used by the solver itself.

Eventually, there will be a way to generically call solvers using common functions and data structures. However, this is to be defined entirely in Conjure Oxide and should not affect how the solver crates are written. See Solver Adaptors.

This section had been taken from the '2023‐11: High Level Plan' page of the conjure-oxide wiki

2024‐03: Implementing Uniplates and Biplates with Structure Preserving Trees

Contents:

- Recap: Uniplates and Biplates

- Definition of Children

- Storing The Structure of Children

- Uniplates and Biplates Using Structure Preserving Trees

Comments and discussion about this document can be found in issue #261.

In #180 and #259 we implemented the basic Uniplate interface and a derive macro to automatically implement it for enum types. However, our current implementation is incorrect and problematic: we have defined children wrong; and our children list does not preserve structure, making more complex nested structures hard to recreate in the context function.

Recap: Uniplates and Biplates

A quick recap of what we are trying to do - for details, see the Uniplate Haskell docs, our Github Issues, and the paper.

Uniplates are an easy way to perform recursion over complex recursive data types.

It is typically used with enums containing multiple variants, many of which may be different types.

data T = A T [Integer]

| B T T

| C T U

| D [T]

With Uniplate, one can perform a map over this with very little or no boilerplate.

This is implemented with a single function uniplate that returns a list of children of the current object and a context function to rebuild the object from a list of children.

Biplates provide recursion over instances of type T within some other type U. They are implemented with a single function biplate of similar type to uniplate (returning children and a context function).

These functions are able to be implemented on any data type through macros making Uniplate operations boilerplate free.

Definition of Children

We currently take children of T to mean direct descendants of T inside T. However, the correct definition of children is maximal substructures of type T.

For example, consider these Haskell types:

data T = A T [Integer]

| B T T

| C T U

| D [T]

data U = E T T

| F Integer

| G [T] T

Our current implementation would define children as the following:

children (A t1 _) = [t1]

children (B t1 t2) = [t1, t2]

children (C t1 u) = [t1]

children (D ts) = ts

However, the proper definition should support transitive children - i.e. T contains a U which contains a T:

children (A t1 _) = [t1]

children (B t1 t2) = [t1, t2]

children (C t1 (E t2 t3)) = [t1,t2,t3]

children (C t1 (F _)) = [t1]

children (C t1 (G ts t3)) = [t1] ++ ts ++ [t3]

children (D ts) = ts

While a seemingly small difference, this complicates how we reconstruct a node from its children: we now need to create a context that takes a list of children and creates an arbitrarily deeply nested data structure containing multiple different types. In particular, the challenge is keeping track of which elements of the children list go into which fields of the enum we are creating.

We already had this problem dealing with children from lists, but a more general approach is needed.

Storing The Structure of Children

How do we know which children go into which fields of the enum variant?

For example, consider this complicated instance of T:

data T = A T [Integer]

| B T T

| C T U

| D [T]

data U = E T T

| F Integer

| G [T] T

myT = C(D([t0,...,t5),G([t6,...,t12],t13))

Its list of children is: [t0,...,t13].

Try creating a function to recreate myT based on a new list of children. Hint: it is difficult, and even more so in full generality!

If we instead consider children to be a tree, where each field in the original enum variant is its own branch, we get:

data Tree A = Zero | One A | Many [(Tree A)]

myTChildren =

Many [(Many [One(t0),...,One(t5)]), -- C([XXX], _) field 1 of C

(Many [ -- C([_],XXX) field 2 of C

(Many [One(t6),...,One(t12)]), -- G([XXX],_) field 2.1 of C

(One t13))] -- G([_],XXX)) field 2.2 of C

This captures, in a type-independent way, the following structural information:

myThas two fields.- The first field is a container of Ts.

- The second field contains two inner fields: one is a container of Ts, one is a single T.

Representing non-recursive and primitive types

Often primitive and non-recursive types are found in the middle of enum variants. How do we say “we don’t care about this field, it does not contain a T” with our Tree type? Zero can be used for this.

For example:

data V = V1 V Integer W

| V2 Integer

data W = W1 V V

myV = (V1

(V2 1)

1

(W1

(V2 2)

(V2 3)))

myVChildren =

(Many [

(One v1), -- V1(XXX,_,_)

Zero, -- V1(_,XXX,_)

(Many [ -- V1(_,_,XXX)

(One v2),

(One v3)

]))

This additionally encodes the information that the second field of myV has no Ts at all.

While this information isn’t too useful for finding or traversing over the target type, it means that the tree structure defines the structure of the target type completely: there are always the same number of tree branches as there are fields in the enum variant.

Uniplates and Biplates Using Structure Preserving Trees

Recall that the uniplate function returns all children of a data structure alongside a context function that rebuilds the data structure using some new children.

To implement this, for each field in an enum variant, we need to ask the questions: “how do we get the type Ts in the type U”, and "how can we rebuild this U based on some new children of type T?".

This is just a Biplate<U,T>, which gives us the type T children within a type U as well as a context function to reconstruct the U from the T.

Therefore:

-

We build the children tree by combining the children trees of all fields of the enum (such that each field’s children is a branch on the tree).

-

We build the context function by calling each fields context function on each branch of the input tree.

This is effectively a recursive invocation of Biplate.

What happens when we reach a T? Under the normal definition, Biplate<T,T> would return its children. This is wrong - we want to return T here, not its children!

When T == U we need to change the definition of a Biplate: Biplate<T,T> operates over the input structure, not its children.

For our example AST:

data T = A T [Integer]

| B T T

| C T U

| D [T]

data U = E T T

| F Integer

| G [T] T

Here are some Biplate and Uniplates and their resultant children trees:

-

Biplate<Integer,T> 1isZero. -

Uniplate<T> (A t [1,2,3])is(Many [Biplate<T,T> t ,Zero]).This evaluates to

(Many [(One t),Zero]) -

Biplate<T,T> tisOne t. -

Biplate<T,U> (G ts t1)is(Many [Biplate<T,[T]> ts , Biplate<T,T> t ]).This evaluates to

(Many [(Many [(One t0),...(One tn)]),(One t)]) -

Uniplate<T,T> (C t (G ts t1))is(Many [Biplate<T,T> t, Biplate<U,T> (G ts t1))This evaluates to

(Many [(One t), (Many [(Many [(One t0),...,(One tn)]), (One t)]))

This section had been taken from the '2024‐03: Implementing Uniplates and Biplates with Structure Preserving Trees' page of the conjure-oxide wiki

Expression rewriting, Rules and RuleSets

NOTE: Once the rewrite engine API is finalized, we should possibly make a separate page for it

Overview

Conjure uses Essence, a high-level DSL for constraints modelling, and converts it into a solver-specific representation of the problem. To do that, we parse the Essence file into an AST, then use a rule engine to walk the expression tree and rewrite constraints into a format that is accepted by the solver before passing the AST to a solver adapter.

The high-level process is as follows:

- Start with a deterministically ordered list of rules

- For each node in the expression tree:

- Find all rules that can be applied to it

- If there are none, keep traversing the tree. Otherwise:

- Take the rules with the highest priority

- If there is only one, apply it

- If there are multiple, use some strategy to choose a rule (The rule selection logic is separate from the rewrite engine itself) For testing, we currently just choose the first rule

- When there are no more rules to apply, the rewrite is complete

We want the rewrite process to:

- be flexible - instead of hard coding the rules, we want an easy way to extend the list of rules and to decide which rules to use, both for ourselves and for any users who may wish to use conjure-oxide in their projects

- be deterministic (in a loose sense of the term) - for a given input, set of rules, and a given set of answers to all rule selection questions (see above), the rewriter must always produce the same output

- happen in a single step, instead of doing multiple passes over the model (like it is done in Saville Row currently)

Rules

Overview

Rules are the fundamental part of the rewrite engine. They consist of:

- A unique name

- An application function which takes an

Expressionand either rewrites it or errors if the rule is not applicable. (checking applicability and applying the rule are not separated to avoid code duplication and inefficiency - their logic is the same)

We may also store other metadata in the Rule struct, for example the names of the RuleSet's that it belongs to

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { pub struct Rule<'a> { pub name: &'a str, pub application: fn(&Expression) -> Result<Expression, RuleApplicationError>, pub rule_sets: &'a [(&'a str, u8)], // (name, priority). At runtime, we add the rule to rulesets } }

Registering Rules

The main way to register rules is by defining their application function and decorating it with the #[register_rule()] macro.

When this macro is invoked, it creates a static Rule object and adds it to a global rule registry. Rules may be registered from the conjure_oxide crate, or any downstream crate (so, users may define their own rules)

Currently, the register_rule macro has the following syntax:

#[register_rule(("<RuleSet name>", <Rule priority within the ruleset>))]

Example

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { use conjure_core::ast::Expression; use conjure_core::rule::RuleApplicationError; use conjure_rules::register_rule; #[register_rule(("RuleSetName", 10))] fn identity(expr: &Expression) -> Result<Expression, RuleApplicationError> { Ok(expr.clone()) } }

Getting Rules from the registry

Rules may be retrieved using the following functions:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { pub fn get_rule_by_name(name: &str) -> Option<&'static Rule<'static>> }

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { pub fn get_rules() -> Vec<&'static Rule<'static>> }

get_rules()returns a vector of static references toRulestructsget_rule_by_name()returns a static reference to a specific rule, if it exists

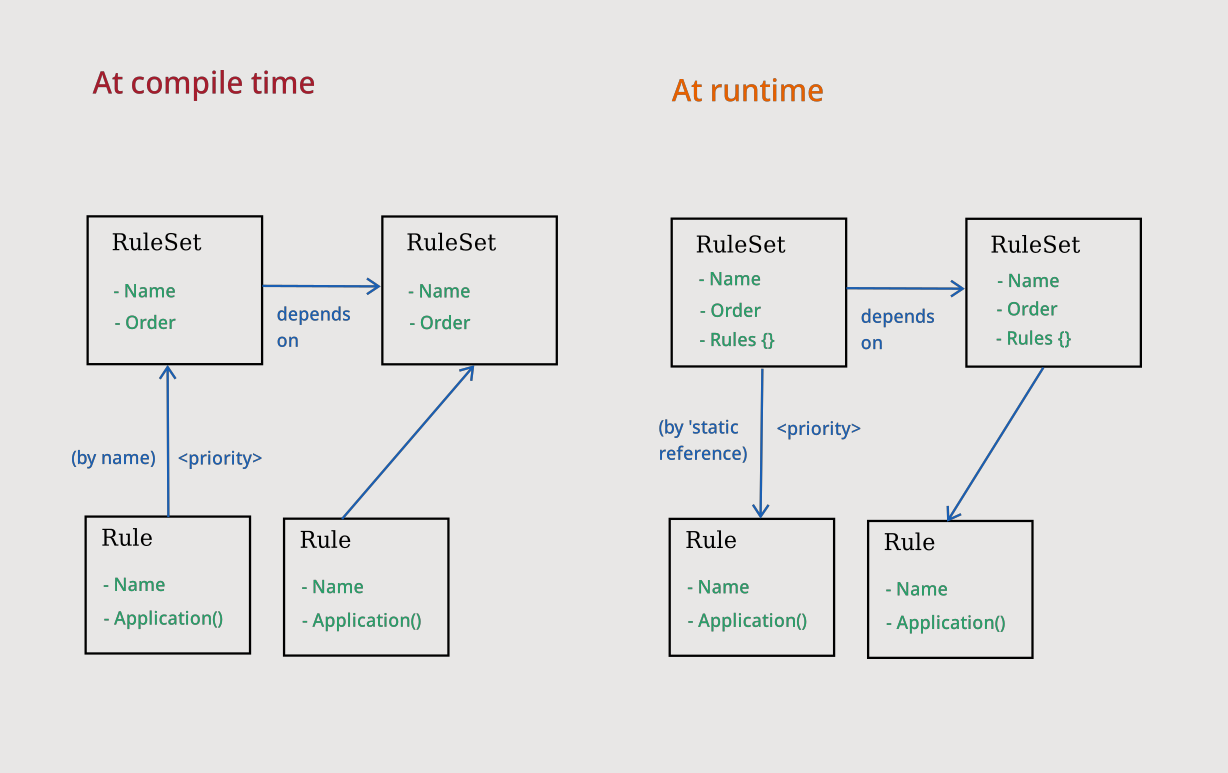

Rule Sets

Rule sets group some Rules together and map them to their priorities.

The rewrite function takes a set of RuleSet's and uses it to resolve a final list of rules, ordered by their priority.

The RuleSet object contains the following fields:

nameThe name of the rule set.orderThe order of the rule set.rulesA map of rules to their priorities. This is evaluated lazily at runtime.solversThe solvers that this RuleSet applies forsolver_familiesThe solver families that this RuleSrt applies for

NOTE: A

RuleSetwould apply if EITHER of the following is true:

- The target solver belongs to its list of

solvers- The target solver belongs to a family that is listed in

solver_families, even if it is not explicitly named insolvers

It provides the following public methods:

get_dependencies() -> &HashSet<&'static RuleSet>Get the dependencyRuleSets of thisRuleSet(evaluating them lazily if necessary)get_rules() -> &HashMap<&'a Rule<'a>, u8>Get a map of rules to their priorities (performing lazy evaluation - "reversing the arrows" - if necessary)

Registering Rule Sets

Like Rules, RuleSets may be registered from anywhere within the conjure_oxide crate or any downstream crate.

They are registered using the register_rule_set! macro using the following syntax:

register_rule_set!("<Rule set name>", <order>, ("<name of dependency RuleSet>", ...), (<list of solver families>), (<list of solvers>));

If a bracketed list is omited, the corresponding list would be empty. However, you must not break the order. For example:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { register_rule_set!("MyRuleSet", 10) // This is legal (rule set will have no dependencies, solvers or solver families) register_rule_set!("MyRuleSet", 10, ("DependencyRS")) // Also legal register_rule_set!("MyRuleSet", 10, (SolverFamily::CNF)) // This is illegal because dependencies come before solver families register_rule_set!("MyRuleSet", 10, (), (SolverFamily::CNF)) // But this is fine }

Example

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { register_rule_set!("MyRuleSet", 10, ("DependencyRuleSet", "AnotherRuleSet"), (SolverFamily::CNF), (SolverName::Minion)); }

Adding Rules to RuleSets

Notice that we do not add any rules to the RuleSet when we register it.

Instead, the Rule contains the names of the RuleSets that it needs to be added to.

At runtime, when we first request the rules from a RuleSet, it retrieves a list of all the rules that reference it by name from the registry, and stores static references to the rules along with their priorities.

This is done to allow us to statically initialize Rules and RuleSets in a decentralized way across multiple files and store them in a single registry. Dynamic data structures (like Vec or HashMap) cannot be initialized at this stage (Rust has no "life before main()"), so we have to initialize them lazily at runtime.

Internally, we would sometimes refer to this lazy initialization as "reversing the arrows".

Getting RuleSets from the registry

Similarly to Rules, RuleSets may be retrieved using the following functions:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { pub fn get_rule_set_by_name(name: &str) -> Option<&'static RuleSet<'static>> }

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { pub fn get_rule_sets() -> Vec<&'static RuleSet<'static>> }

Resolving a final list of Rules

Our rewrite function takes an Expression along with a list of RuleSets to apply:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { pub fn rewrite<'a>( expression: &Expression, rule_sets: &Vec<&'a RuleSet<'a>>, ) -> Result<Expression, RewriteError> }

Before we start rewriting the AST, we must first resolve the final list of rules to apply.

This is done via the following steps:

-

Add all given RuleSet's to a set of rulesets

-

Recursively look up all their dependencies by name and add them to the set as well

-

Once we have a final set of

RuleSets:-

Construct a

HashMap<&Rule, priority>). This will hold our final mapping of rules to priorities -

Loop over all the rules of every

RuleSet -

If a rule is not yet present in the final

HashMap, add it and its priority within theRuleSet -

If it is already present:

- Compare the order of the current

RuleSetand the one that the rule originally came from - If the new

RuleSethas a higher order, update theRule's priority

- Compare the order of the current

-

-

Once all rules have been added to the

HashMap:- Take all its keys and put them in a vector

- Sort it by rule priority

- In the case that two rules have the same priority, sort them lexicographically by

name

In the end, we should have a final deterministically ordered list of rules and a HashMap that maps them to their priorities.

Now, we can proceed with rewriting.

Why all this weirdness?

Rule ordering

We want to always have a single deterministic ordering of Rules. This way, for a given set of rules, the select_rule strategy would always give the same result.

Think of it as a multiple choice quiz: if we want to know that the same numbers in the answer sheet actually correspond to the same set of answers, we must make sure that all students get the questions in the same order.

This is why we sort Rules by priority, and then use their name (which is guaranteed to be unique) as a tie breaker.

Normally, one would just construct a vector of Rules and use it as the final ordering, but we cannot do that, because rules are registered in a decentralized way across many files, and when we get them from the rule registry, they are not guaranteed to be in any specific order

RuleSet ordering

As part of resolving the list of rules to use, we need to take rules from multiple RuleSets and put these rules and their priorities in a HashMap. However, the RuleSets may overlap (i.e. contain the same rules but with different priorities), and we want to make sure that, for a given set of RuleSets, the final rule priorities will always be the same.

Normally, this would not be an issues - entries in the HashMap would be added and updated as needed as we loop over the RuleSets. However, since the RuleSets are stored in a decentralised registry and are not guaranteed to come in any particular order (i.e. this order may change every time we recompile the project), we need to ensure that the order in which the entries are added to the HashMap (and thus the final rule priorities) doesn't change.

To achieve this, we use the following algorithm:

- Loop over all given

RuleSets - Loop over all the rules in a

RuleSet- If the rule is not present in the

HashMap, add it - If the rule is already there:

- If this

RuleSethas a higherorderthen the one that the rule came from, update its priority - Otherwise, don't change anything

- If this

- If the rule is not present in the

NOTE: The

orderof aRuleSetshould not be thought of as a "priority" and does not affect the priorities of the rules in it. It only provides a consistent order of operations when resolving the final set of rules

This section had been taken from the 'Expression rewriting, Rules and RuleSets' page of the conjure-oxide wiki

Semantics of Rewriting Expressions with Side‐Effects

Overview

When rewriting expressions, a rule may occasionally introduce new variables and constraints. For example, a rule which handles the Min expression may introduce a new variable aux which represents the minimum value itself, and introduce constraints aux <= x for each x in the original Min expression. Conjure and Conjure Oxide provide similar methods of achieving these "side-effects".

Reductions

In Conjure Oxide, reduction rules return Reduction values. These contain a new expression, a new (possibly empty) set of top-level constraints, and a new (possibly empty) symbol table. The two latter values are brought up to the top of the AST during rewriting and joined to the model. These reductions, or "local sub-models" therefore can define new requirements which must hold across the model for the change that is made to a specific node of the AST to be valid.

The example with Min given in the overview is one case where plain Reductions are used, as a new variable with a new domain is introduced, along with constraints which must hold for that variable.

Bubbles

Reductions are not enough in all cases. For example, when handling a possibly undefined value, changes must be made in the context of the current expression. Simply introducing new top-level constraints may lead to incorrect reductions in these cases. The Bubble expression and associated rules take care of this, bringing new constraints up the tree gradually and expanding in the correct context.

Essentially, Bubble expressions are a way of attaching a constraint to an expression to say "X is only valid if Y holds". One example of this is how Conjure Oxide handles division. Since the division expression may possibly be undefined, a constraint must be attached to it which asserts the divisor is != 0.

An example of division handling is shown below. Bubbles are shown as {X @ Y}, where X is the expression that Y is attached to.

!(a = b / c) Original expression

!(a = {(b / c) @ c != 0}) b/c is possibly undefined, so introduce a bubble saying the divisor is != 0

!({(a = b / c) @ c != 0}) "bubble up" the expression, since b / c is not a bool-type expression

!(a = b / c /\ c != 0) Now that X is a bool-type expression, we can simply expand the bubble into a conjunction

Why not just use Reductions to assert at the top-level of the model that c != 0? In the context of undefinedness handling, the final reduction is dependent on the context it occurs in. In the above example, if we continue by simplifying (apply DeMorgan's), we can see that it becomes a != b / c \/ c = 0. Thus, c = 0 is a valid assignment for this example to be true, and setting c != 0 on the top-level would be incorrect.

In Conjure Oxide, Bubbles are often combined with the power of Reductions to provide support for solvers like Minion.

This section had been taken from the 'Semantics of Rewriting Expressions with Side‐Effects' page of the conjure-oxide wiki

Ideal Scenario of Testing for Conjure-Oxide (Dec 2024)

Introduction

What is the goal of this document?

The goal of this document is to provide an ideal testing outline for Conjure-Oxide, a project in development. To do so, this document will be split into definitions (of Conjure-Oxide and other relevant components, as well as key testing terms), current Conjure-Oxide testing, and idealised (to an extent) Conjure-Oxide testing. When discussing idealised testing, any key limitations will also be discussed. Further, this document will address the use of GitHub actions in this project, including code coverage.

What is Conjure-Oxide

Conjure-Oxide is a constraint modelling tool which is implemented in Rust. Of note, it is a reimplementation of the Conjure automated constraint modelling tool and the Savile Row Modelling Assistant, functionally merged and rewritten in Rust - largely because Rust is an efficient high-performance language. Conjure-Oxide takes in a problem written in a high level constraint language, which is called Essence, and creates a model from this. This model is then transformed into a solver-friendly form, and solved using one of the available back-ends. At the moment, these solver back-ends include Minion (a Constraint Satisfiability Problem (CSP) solver) and in-development translation and bindings to a SAT (Propositional Satisfiability Problem) solver. To put it simply, Conjure-Oxide is a compiler to different modelling languages, the result of which is passed into the respective solver. These solvers act as back-ends and must be given bindings to Conjure-Oxide, but are not actually part of it themselves.

How is the model made 'solver-friendly'?

Conjure-Oxide has a rule engine, which applies rules onto the model passed in as Essence, to lower the level of the language into one which can be parsed and solved by the back-end solvers. This engine applies rewriting rules, such as (x = - y) to (x + y = 0), to transform the model. As Essence is a fairly high-level language, with compatibility for sets and matrices and a number of keywords, there are a lot of rewrite rules which may be needed before the model can be passed into a solver. This translation is one of the key roles of Conjure-Oxide, and this rule application refines the language from a higher level to a lower level. The exact rules applied and the degree of simplification varies on the language requirement of the solver: for example, Minion has higher-level language compatibility than a SAT solver1.

Conjure and Savile Row

Also relevant to the testing of Conjure-Oxide is Conjure and Savile Row 2. This is because as Conjure-Oxide is a merge and reimplementation of these programs, the testing can be performed comparatively against Conjure and Savile Row. When this document uses the term "Conjure suite", it refers to both Conjure and Savile Row, being used in combination, generally using the Minion solver. Where there is deviation from this, it will be explicitly clarified.

What is Conjure?

Conjure is a constraint modelling tool, implemented in Haskell. It uses a rule engine similarly to Conjure-Oxide to simplify from Essence to Essence' (a subset of Essence which is slightly lower-level), and this "refinement" produces the lower-level model to pass to Savile Row.

What is Savile Row?

Savile Row is a constraint modelling assistant which translates from Essence' to a solver-friendly language. Alongside translating the model to the target language, it can reformat the model with an additional set of rules. This provides a performance increase by improving the model itself. Functionally, the better a model is, the faster a solver will solve it.

What is Minion?}

Minion is a Constraint Satisfiability Problem solver, which has bindings to both Conjure suite and Conjure-Oxide. Minion is a fast, scalable, CSP solver, designed to be capable of solving difficult models while still being time optimised. This is the main solver in use by both the Conjure suite and by Conjure-Oxide, due to its flexibility and efficiency.

Definitions for Testing

Two main forms of testing will be addressed within this document: correctness testing and performance testing. Fuzz testing (inputting malformed instances to see the program response) is not currently intended as part of testing Conjure-Oxide, and so will not be outlined or addressed. Metamorphic testing may have applications to this project, and so will be defined, but will not be considered as part of the ideal implementation at present as it is not possible to implement at this point in time.

What is correctness testing?

In the field of computer science, correctness can be formally defined as a program which behaves as expected by it's formal specification, in all cases. As such, testing for correctness essentially consists of testing that the program produced the correct result for all given test cases. Correctness testing does not require exhaustiveness (checking all inputs on all states), but instead requires testing that all (or most) states function with varied inputs, which can then be used as a proof of correctness.

What is performance testing?

Performance testing refers to a range of methodologies designed to measure or evaluate a software's performance. By performance, this generally refers to time taken to complete a process and the stability under load. The time taken for processes will vary not only by system, but also by device depending on factors such as background processes. As not all performance testing methodologies are relevant to Conjure-Oxide, they will not be outlined in this document. The two most common forms of performance testing are load testing and stress testing. Load testing examines the performance of a program to support its expected usage, and is used to identify bottlenecks in software, as well as possibly identify a relationship of usage to time. Stress testing places the program under extremely high load to see the ability of the software to function under exceptional load. This is generally used to find the functional upper load of a program before it breaks.

What is metamorphic testing?

Most tests use oracles, where the answer is known and is explicitly checked against. This is what is done in correctness testing, as laid out above. Metamorphic testing, instead, uses Metamorphic relations to generate new test cases from existing previous ones. A metamorphic relation is the relation between the test (the inputs) and the result (the outputs). An example of this is (sin(x) = sin( \pi -x)), where, regardless of x, there is a consistent relation between the input and output. As such, test cases can be generated to test the correctness of this output.

Test Scenario for Conjure-Oxide

As Conjure-Oxide is a reimplementation, it is possible to perform a large amount of the testing comparatively. By this, it means that testing can be done independently on Conjure-Oxide, and the results can be directly compared against the results of the same test being ran in the Conjure suite. This is true not only for the correctness testing, but also for the performance testing. Tests run in the Conjure suite are run by Conjure, which uses Savile Row and the required solvers to produce the correct output.

Correctness Testing

There are several areas which should be tested for correctness in Conjure-Oxide: that the Essence is correctly parsed; that the correct Essence translation is generated; that the correct rules are applied in the correct order; and finally that the correct solution is reached by Minion. For something to be 'correct' in Conjure-Oxide, it means it must behave as expected. As Conjure-Oxide reimplements Conjure and Savile Row, the expected behaviour is that of the Conjure suite. As such, correctness testing is performed exclusively comparative to the results produced by this suite. Correctness testing as implemented is looking to ensure that all expected files match the files which are actually produced. Where there is a difference, the initial assumption is that Conjure-Oxide has the mistake. This is not necessarily always correct - the Conjure suite may have bugs or areas where it is not producing the expected outcome - but usually is.

Current Correctness Testing

Correctness testing is the main form of testing performed in Conjure-Oxide at present, mainly through integration testing. Integration testing tests how the whole application works together as a whole, and as such is the most applicable to test all areas of testing needing to be done in Conjure-Oxide. In the current testing implementation, a test model is produced, and then the parse, rule-based transformation and result file are compared against those produced by calling the same test case on Conjure. In this, we assume that the result produced by the Conjure suite is always going to be correct. Theoretically, this is completely functional - as Conjure-Oxide is a reimplementation, any bugs which exist in Conjure or Savile Row could also exist in Conjure-Oxide without causing Conjure-Oxide to violate it's correctness. However, this defeats the point of an evolving project, so assuming the complete correctness of the Conjure suite is not sufficient for testing.

Comparative Correctness Testing

As it is possible to perform the testing comparatively, the current implementation forms a functional basis for any ideal implementation, because it is built on this comparison. The current implementation functions well (although with limitations, as addressed below) in showing a degree of correctness, however it is not necessarily holistic enough to show the full correctness of the project. The primary solution for this issue is simply increasing the test coverage through developing a broader repository of models to be tested. Conjure has a very broad set of translation rules, meaning that there is a large number of rules which can be reimplemented in Conjure-Oxide. This enables a demonstration of the functionality of Conjure-Oxide in more scenarios, by ensuring not only are all rules tested individually, but rules in combination, with specific priority, are also tested and return results as expected. There may be some benefit to having tests that are not solved and compared against results from the Conjure suite, but rather solved independently (e.g., by mathematicians) and then compared to the results of the same model produced by Conjure-Oxide. By proving these results as correct, it is possible to go beyond simply assuming Conjure and Savile Row are always right. However, this is not particularly feasible in a broader implementation and would be fairly limited in scale due to this, especially as Conjure-Oxide is not a large project. Solver Testing Part of the larger Conjure-Oxide project is the implementation of a Satisfiability (SAT) solver. This implementation will require integration testing alongside the rest of the Conjure-Oxide project. As Conjure has a SAT solver, this is possible to be done comparatively, although would require the implementation of the ability to select a specific solver to solve a model. The comparative testing would simply compare the translated essence to SAT, and the output of the Conjure suite's SAT solver to that of the Conjure-Oxide SAT solver, and debug where the tests do not pass.

Limitations of Correctness Testing

Conjure-Oxide is, in part, a refinement based program. A large part of it's function is to refine from Essence down to a solver-friendly language. One part of the way that this is done in Conjure-Oxide is through a rule engine. This rule engine applies modifications to the constraints problems given to the project. At current, we just assume the rules applied are true. For example, (x = -y + z) becoming (x + y - z = 0) is a simple transformation which could be made by the rule engine. We do not formally prove that this transformation is correct, we just assume that it is the correct transformation. In simpler transformations such as this one, that is a valid assumption - it is possible to confirm that the modification is correct with minimal effort. In cases where more complex rules may be applied, the lack of a proof poses a limitation on the project. In an ideal scenario, this limitation could be removed by having proofs for every single rule applied in the rule engine, therefore not having to rely on an assumed correctness. Another of the primary limitations in correctness testing as implemented is that it assumes that the output being produced by Minion (or the SAT solver in development) is correct. As there are no known bugs in Minion, this is an acceptable assumption to make. That said, it is not necessarily accurate that all output from Minion is correct. Other mature (having existed, and been used and updated, over a protracted period of time), state of the art solvers can produce incorrect results3.

If Minion has similar unknown bugs, it may fail to fulfil the correctness element of correctness testing. The SAT solver which is being implemented is in it's infancy and as such is much less reliable. It is likely that it will have a number of bugs and logical errors which will be gradually harder to find as time goes on (operating under the assumption that easy-to find and solve bugs will be removed earlier, leaving only more hidden or complex bugs).

Performance Testing

It is of note that a large motivation behind the reimplementation of the Conjure suite into a single Rust program is to improve the performance of the compilation from Essence to a solver-friendly language, without compromising on the time taken to solve a model. Currently, Conjure translates Essence into Essence', and then Savile Row refines and reformats the resultant Essence' into a solver-friendly language. Conjure-Oxide translates directly from Essence into a solver-friendly language, which should cut down on the amount of steps necessary and as such result in a shorter translation time. When testing for overall performance of Conjure-Oxide, the primary metrics that we are are concerned with is the total time taken for a model to be parsed, translated, and solved through the solver back-end. This total time can be split into two components: the translation time and the time taken by the solver. We can also use solver nodes as a measure of performance of the solver, as the time the solver takes may vary depending on background processes. In the performance testing addressed in this document, though there will be consideration for the solver time, the primary measurement of value is translation time.

Current Performance Testing

At present, there is no formal performance testing implemented in Conjure-Oxide. While stats files are generated on each test run, tracking a number of fields (rewrite time, solver time, solver nodes, total time, etc.), nothing is done with this information. As such, while there is some measure of 'performance', it lacks context, is not reliable (since data is produced from a single run) and overall does not create a measure of Conjure-Oxide's performance. Performance testing, both load and stress based, can be performed both comparatively (as in checking speed or efficiency of one program directly against another (or several other) programs), but also individually on the given program. As such, both 'methods' of Performance testing will be discussed.

Performance Testing of just Conjure-Oxide

Sole examination of the performance of Conjure-Oxide cannot show whether there is a performance improvement as desired. However, the goal of individual performance testing is rather to enable the development of a relationship between complexity (of translation) and time (to translate). In addition, this will allow for the identification of any notable bottlenecks in the program, allowing these specific problem areas to be targeted for improvement. To performance test a program, a number of things need to be established. Firstly, what the metric(s) are being considered - as established above, for Conjure-Oxide this is the translation-, and to some degree solver-, time. Secondly, what is the independent variable - as in, what is being varied to result in different outputs. In Conjure-Oxide, this will be size or complexity of a given Essence file. Size and complexity will be defined contextually below.

Distinction between Size and Complexity

Size and complexity of a given Essence file are separate, although certainly correlated. Put simply, size refers more directly to the number of components that make up an Essence input problem, whereas complexity refers to specific aspects which complicate translation, rather than directly increase its size. When applying rules to a model, the rules are applied by priority. The implementation of this is essentially that each rule is checked against the model, and if it applies, it is applied to transform the model in order of priority (e.g., two rules are valid, the higher priority rule is the one selected). Use of a dirty-clean (this will not try to apply rules to a finished model) or naive (this will try and apply all rules until they have all been checked, applied, checked again, etc.) rewriter will also result in variance on translation time, so when experiments are being defined it is best to account that all models are using the same version of the rewriter. Size refers to the number of variables, constraints, or size of input data (for example, a larger set or array) given as part of an input file. A 'larger' problem has more constraints and variables than a 'smaller' one. This will impact translation time (the relationship of this change should be examined by the performance testing) because there is more to parse and translate, even if the actual rule application is simple. On the other hand, in this context, complexity can be loosely defined as elements of the model which make it difficult to translate, without regard for the size. Features which could increase complexity include nesting, conditional constraints, dynamic constraints, etc. When testing for size, it is best to use very simple, repeated rules, and when testing complexity it is best to try to ensure that this is not also linked into increasing size, although these two features are tied together and therefore difficult to isolate from one another.

Performance Experiments to run

There are two main types of experiment to be considered in the performance testing of Conjure-Oxide. \textbf{Load testing}, where the size or complexity is varied in order to measure translation time under different conditions; and \textbf{stress testing}, specifically to see whether higher complexity or larger files disproportionately increase translation time. As stress testing requires some measure of what is proportional and what is not, load testing is addressed first.

Load testing for Conjure-Oxide

When designing performance testing for a system, there are several considerations to be made. Primarily, it is of importance that data gathered and aggregated is suitable to be used for graphing and building relationships. To do this, data must be reliable, consistent and accurate. Single runs of data cannot provide this, as many factors may influence the results. In order to fulfil these needs, substantial amounts of data should be gathered. Anomalies should be removed (for example, using interquartile range or using Z-Scores) or simply averaged over (this is less accurate but more achievable). As size or complexity varies, these averaged results should be plotted into a graph. This is the most effective way of providing understanding of the relationship between size/complexity and translation time.

Stress testing for Conjure-Oxide

Once a relationship has been established by load testing, stress testing can occur. Although it is possible to see the point at which a program fails without prior load testing, having determined the relationship between size/complexity and time allows for a consideration of what is disproportionate. Implementing this in Conjure-Oxide would simply involve the program under abnormally high load to find it's breaking point, using repeated results to ensure reliability and accuracy of the data.

Additional Performance Profiling

Many parts of Conjure-Oxide (such as specific rules, string manipulations, memory allocation to solvers, etc.) are also not capable of being directly examined for their complexity, and the complexity of these things cannot be manipulated to perform experiments as outlined above. However, it is important that these are still being tested for their performance. This is because it is important to catch irregular memory allowances, excessive time spending, expensive Rust functions, etc., in order to ensure that Conjure-Oxide runs both as quickly and as smoothly as possible, One way to do this is to run profilers, such as Perf, which allow for the areas that time or memory is being spent to be analysed more specifically. Given this analysis, it is then possible to examine these areas for improvements, as was done in Issue #2884.

Comparative Performance Testing

As established, Conjure-Oxide is a reimplementation of a pre-existing set of programs, these being Conjure and Savile Row. One of the primary goals of this reimplementation is to improve the performance of Translation time, while also ensuring that the time taken to solve a given essence problem is not worsened. Considering that Minion is simply rebound to Conjure-Oxide, much as it was in the Conjure suite, it is unlikely that these bindings would be responsible for a slower solve time. As such, the primary impact on solve time is the model passed into the solver. A worse model will take substantially more time than a model which has been well translated and refined, and substantial increases in the time taken to solve should be avoided. Performance testing should be performed on the Conjure suite (primarily on Savile Row, since the time of Conjure is amortised over each instance) to establish the relationship of size/complexity to time, as in Conjure-Oxide. The results of both may then be plotted on one graph, to see at which point(s) Conjure-Oxide is faster than Savile Row at translation, and vice versa. Comparative testing also allows for the solver nodes (which represent, to some degree, solver time) from both the Conjure suite and Conjure-Oxide. As established, the goal of Conjure-Oxide is to improve translation performance without sacrificing solving performance. As such, it is vital to also consider at which size/complexity of translation the solver nodes start to vastly differ between Conjure suite and Conjure-Oxide, and to examine the rules to see why this is (and whether there is a requisite decrease in translation time which could possibly balance this increase). Though having a small number of nodes which differ (e.g., by 10) is not an issue, when there is a large disparity between number of solver nodes, this reflects poorer quality translation or (possibly) an issue with the binding to Rust.

Limitations of Performance Testing

One limitation of performance testing is the impact that other processes running on the computer or server when testing. Other processes running at the same time mean that less threads can be allocated to Conjure-Oxide or its solver backends when dealing with a model, and as such slow down the speed at which these models can be parsed, translated, and solved. However, this is mainly removed as an issue by a combination of repeated runs, and identifying and removing anomalies (using Z-Score). Another issue present in performance testing is that completely decoupling size and complexity is rather difficult, if not entirely impossible. This is because there is overlap in the definitions, and because as a model becomes more complex, it often becomes larger, and vice versa. Although fully separating these two metrics is the aim in an ideal scenario, an actual implementation would struggle to follow through with this requirement.

GitHub Actions and Testing

GitHub Actions allow for integration of the CI'/CD pipeline to GitHub and the automation of the software development cycle. Automated workflows can be used to build, test and deploy code into a GitHub VM, allowing for flexibility in the development of a project.

What is a workflow?

In GitHub Actions, a workflow is an automated process which is set up within a GitHub repository with the aim to accomplish a specific task. They are triggered by an Event, such as pushing or pulling code. Workflows are made up of the combination of a trigger (the Event) and a set of processes (made up of Jobs, which are sets of steps in a workflow).

Test Rerun

This involves the automated rerunning of tests when a push or pull request is made on the GitHub repository. This is already implemented in Conjure-Oxide, through "test.yml". Test.yml runs tests every push request made to the main branch, and on all pull requests. This allows for correctness testing to be performed on all pushes made to the main, to ensure that no additional tests fail.

Code Coverage

When pushes are made to the main branch of Conjure-Oxide on GitHub, a code coverage automated workflow is run. This workflow generates a documentation coverage report which outlines what percentage of the code in the repository is being executed when tests are run. The higher the percentage, the more of the code can be relied upon as working under test conditions. This is also already implemented in the GitHub repository, through "code-coverage.yml", "code-coverage-main.yml" and "code-coverage-deploy.yml". One of the goals of correctness testing is to increase the code coverage percentage, because this would show that more of the code is functioning correctly.

Automated Performance Testing

GitHub workflows can be used to create further custom processed to be automated. Automating performance testing in GitHub allows for them to be run routinely (e.g., every X pushes, or every X days) to ensure consistent performance of the project. As they occur automatically, this means that benchmarks can be set, and failue on any of these benchmarks can reuslt in a flag, allowing for early detection when performance of the program begins to regress, or fall far behind that of the Conjure suite. GitHub Actions allow for the results to be placed into files, and from here an interactive dashboard could be generated (as in PR #291. 5

Brief Outline of Possible Future Sub-Projects

Having outlined at least a portion of the ideal testing scenario above, as well as some limitations of this scenario, it is now possible to outline to some degree future sub-projects which could be added to the overall Conjure-Oxide project.

Improving Code Coverage

One method of improving the code coverage is by creating a broader repository of integration tests. This project focuses on the correctness aspect of the testing, and in itself can be split into several sub-projects or subsumed into other projects (e.g., if someone is writing a parser, they may decide to write the tests for this parser). The code coverage report is updated every-time a PR is made, and by examining the coverage report (see: {Code Coverage Report}), it is possible to see which areas would benefit from additional testing. Although code coverage testing itself is not concerned with correctness, increasing the amount of correctness testing increases code coverage, and so they are related. It may be beneficial to target areas of the code which have a very low line or function coverage, as this is likely easier to increase.

Producing Proofs for Correctness

As established, one of the limitations of the current correctness testing is that there is an assumption of correctness, that being that we either assume the Conjure suite is correct, or we assume that the rules we are applying are correct. These assumptions are largely valid, but do limit the factual correctness of the project. One possible sub-project, which would have a heavy reliance on mathematical knowledge, is to produce these proofs. This does not necessarily have to be exhaustive: in the case of the correctness testing exhausting the proofs would be extremely time consuming, but having proofs to additionally prove correctness overcomes one of the project limitations. In the case of proving the existing rules, though there are a currently increasing set of rules, they are finite, so this may be more manageable as a project.

Measuring Performance Through Load Testing

The outline of this subproject is to fulfil, at least in part, the requirement for performance testing on this project. There are several ways that this could be approached, all of which vary somewhat, so this project is flexible in its details. One method which may be effective regarding performance testing is to use GitHub Actions to automate the performance testing, as outlined in GitHub Actions and Testing. This is because this would allow flexibility and repeated performance testing, as well as the ability to flag early on when there is a performance decrease. To outline this, it would be necessary to make a directory of tests to be run for their performance, and then create the GitHub workflow to repeatedly run tests on that directory and aggregate the translation time. This can then be plotted graphically and statistically analysed.

Comparative Load Testing

This is an extension of the above project, in that it cannot be created until there is a basis of load performance testing. The essential outline of this project is to repeat the above, except aggregating the data from the results of Savile Row's rewriter, and then graph both Conjure-Oxide and Conjure suite together. This will allow for a direct visual comparison, as well as help with statistical analysis. Furthermore, if GitHub Actions are used, it is possible to flag where there is a large degree of difference in rewriter or solver between Conjure suite and Conjure-Oxide.

Benchmark Testing for Performance

Another sub-project which is possible to derive from this document is to benchmark test elements of the project which cannot be done by varied-load testing, as outlined in the Performance Testing section. Tools, such as Perf, can measure benchmarks and find specific problem areas. When problem areas have been found, these can be raised as an issue, and either fixed as part of this sub-project, or given to another member of the project to complete. This kind of benchmark testing will ensure that the entirety of the Conjure-Oxide is running as efficiently as possible.

Possible Stress Testing

There is also the possibility of adding stress testing to see at which point the rewrite engine fails to be able to parse through an extremely long or especially complex model. This can be done following much the same outline as that of \textit{Measuring Performance Through Load Testing}, however rather than gradually changing the load (dictated by size or complexity) on the system, the change is rapid, in order to find the system's point of failure. As with load testing, this may also be automated by GitHub Actions, though this is a lower priority, as the failure point is less likely to change than the overall system performance.

Conclusion

This document outlines definitions relevant for understanding both the project and the types of testing most applicable. A scenario of testing is then produced, which outlines what testing exists and what testing can be added, as well as any large limitations on an implementation of this ideal state. This allows for any individuals working on testing in the future to have a holistic overview of the state of testing on this project. Finally, a number of smaller sub-projects are outlined as a product of this document, aiming to improve the tested-ness of Conjure-Oxide and compare its success as a reimplementation to Conjure and Savile Row. In the future, it may also be worth examining the possibility and likelihood of being able to apply Metamorphic testing to Conjure-Oxide, to ensure consistency in it's results by developing metamorphic relations between input and output. At present, this is not feasible, and although this document is idealised, it is not intended to be entirely unreasonable or detached from the current reality of the project.

This section had been taken from the 'Ideal Scenario of Testing (Dec 2024)' page of the conjure-oxide wiki

-

Ian P. Gent, Chris Jefferson, and Ian Miguel. 2006. MINION: A Fast, Scalable, Constraint Solver. In Proceedings of the 2006 conference on ECAI 2006: 17th European Conference on Artificial Intelligence August 29 -- September 1, 2006, Riva del Garda, Italy. IOS Press, NLD, 98–102. ↩

-

Hussain, B. S. 2017. Model Selection and Testing for an Automated Constraint Modelling Toolchain; Thesis ↩

-

{Berg, J., Bogaerts, B., Nordström, J., Oertel, A., & Vandesande, D. 2023. Certified Core-Guided MaxSAT Solving. \textit{Lecture Notes in Computer Science}, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-38499-8_1 ↩

-